Thoughts on Selling Generative Art

Through my work with Bright Moments, I’ve spoken with numerous artists about how to sell long-form generative art collections. I have now put this advice into an essay to share with a wider audience.

Supply

Supply is the number of onchain outputs produced by a specific algorithm. Before launching a collection, artists often enforce a supply number that caps a collection to a certain number of mints. Knowing this number helps collectors decide whether or not to participate in the primary sale.

There is no magic formula to determine supply; as the artist, you are most familiar with the diversity of the algorithm and best suited to determining the “right” collection size.

Many generative art collections have 100 - 1,000 outputs, but open editions can be larger. To a first approximation, your collection should be roughly equal to the number of outputs your algorithm can produce without repetition. Algorithms that have lots of visual diversity are well suited to larger collection sizes that explore the entire output space. Algorithms that operate within a tighter band may be better suited to smaller collections.

Getting a feel for the right collection size requires visual inspection of the outputs during testing. As a quick hack, create a folder with numbered images and look for when the outputs start to feel similar. Make a note of this number and generate different folders within that range (e.g. 0-999). If you can't consistently produce a diverse set of outputs, consider lowering the collection size. [1]

Once you’ve deployed an algorithm onchain, the marginal cost of producing additional mints is very low. Because of this, it can be beneficial for new artists to skew towards larger collection sizes which help drive awareness through collector driven marketing and a more active secondary market. Generative art sales are an iterated game, so gaining a large audience can set you up for success later, even if the earlier collections are less commercially successful.

However, there is such a thing as going “too big”. Releasing a collection that doesn’t mint out can be detrimental for artists and limit their ability to sell future work. While there are many reasons why a collection might not mint out, the most common are a combination of price and collection size. Releasing smaller collections at a price point that has a high probability of minting out can help drive interest for future sales. [2]

You can also back into supply based on your financial goal for the sale. For example, if you want to raise 10 ETH and plan to sell each piece for 0.1 ETH, the supply should be at least 100. However, keep in mind that larger collection sizes may have a lower average cost per piece.

In short, deciding the supply for a collection is both an art and a science. Your financial goals, the demand from collectors, and the capabilities of the algorithm all factor into the final collection size. When in doubt, choose numbers that increase your chances of minting out at a price point that is fair for collectors and will allow you to continue practicing your craft.

Price

A successful sale should mint out the collection to a diverse group of collectors at a market clearing price.

Here are some things you want to avoid:

- Underpricing the sale, such that it sells out in seconds or creates a race to press the mint button

- Overpricing the sale, such that it remains unminted, requiring a reduction in the stated supply

- Reducing the mint price later on if the collection is unminted

- Creating a sales dynamic where a large percentage of mints go to a small number of actors that have a focus on "flipping"

There are two basic sales mechanics that generative artists often use:

Fixed Price

A fixed price sale is when every token in a collection is sold for a specific price that does not change during the sale. Usually this price is announced prior to the start of the sale. Mints happen on a first-come-first-serve basis until the collection is minted out.

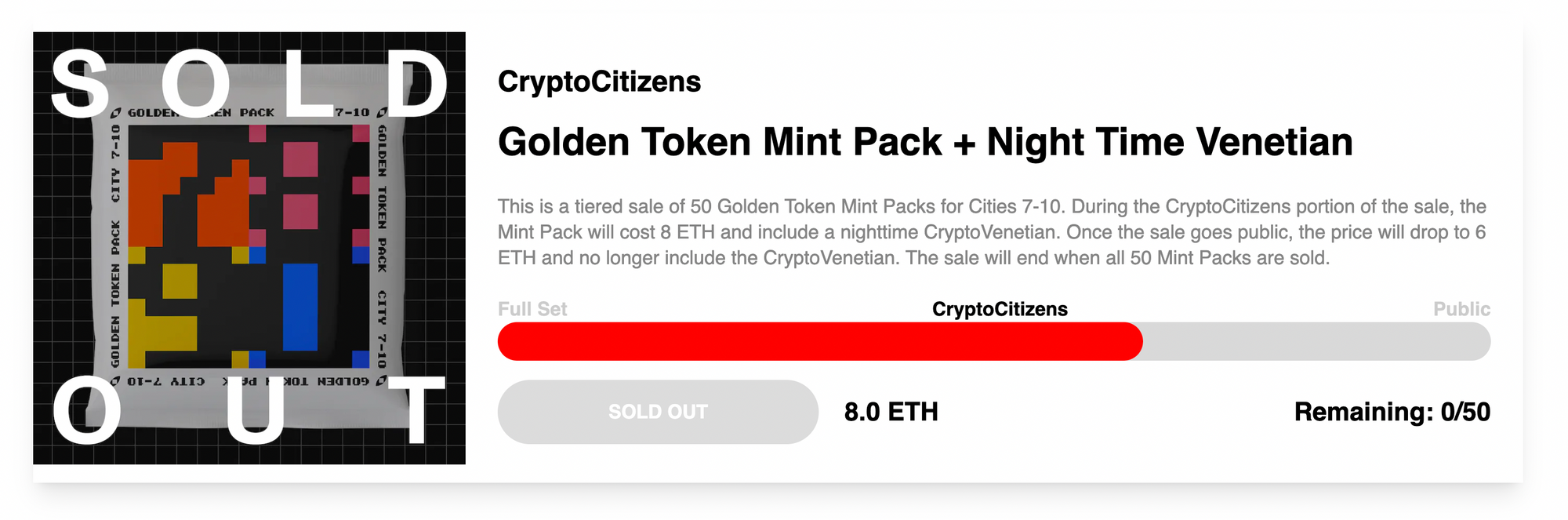

Fixed price sales can be combined with "presales" that allow the artist to restrict minting to a specific group of wallets. Presales should be structured as a series of concentric circles, where access starts among a small group of buyers and gradually increases until there are more potential buyers than available supply. Try to keep presale windows simple, with 2-3 maximum (e.g. friends and family -> prior collectors -> public).

In most cases, fixed price sales should be set slightly below the market clearing price, since there isn't an effective mechanism to lower the price later on.

Auctions

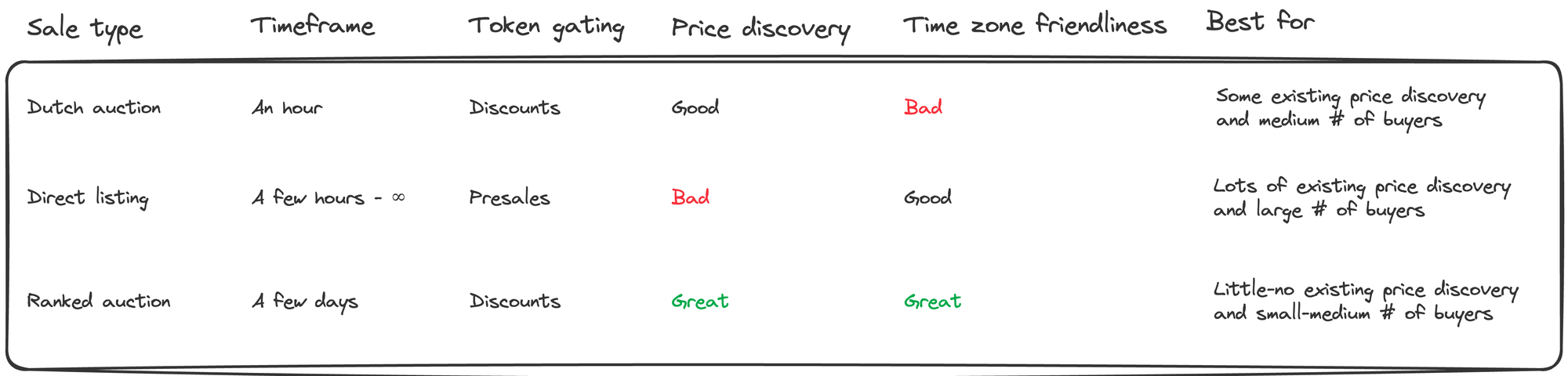

Auctions help encourage price discovery. There are many ways to run an auction, but I'll briefly outline two common formats: dutch and english auctions.

Dutch Auctions

A dutch auction is when the price to mint decreases incrementally over a fixed period of time (e.g. 1 ETH -> 0.1 ETH over 1 hour). Collectors can purchase when the price reaches a level they are comfortable with, assuming the collection has not sold out. The price continues to lower until a "resting price" is met, and the auction usually continues until the collection is sold out. While not perfect, the dutch auction model is used widely throughout the generative art space. It prevents many collectors rushing to buy all at the same time, and generally creates better price discovery for the artist as the market is ultimately deciding the sales price.

Dutch auctions can also include a "rebate", which means that all collectors pay the same clearing price at the end of the sale. This helps ensure fairness among collectors since everyone pays the same price for the mints.

Artists who are using a dutch auction should consider holding back a certain number of mints in reserve, since collectors who are not available during the minting window may lose the opportunity to collect in the primary sale. It's not uncommon to hold back ~5-10% of the collection for the artist to offer to collectors at the sellout price after the auction has concluded.

English Auctions

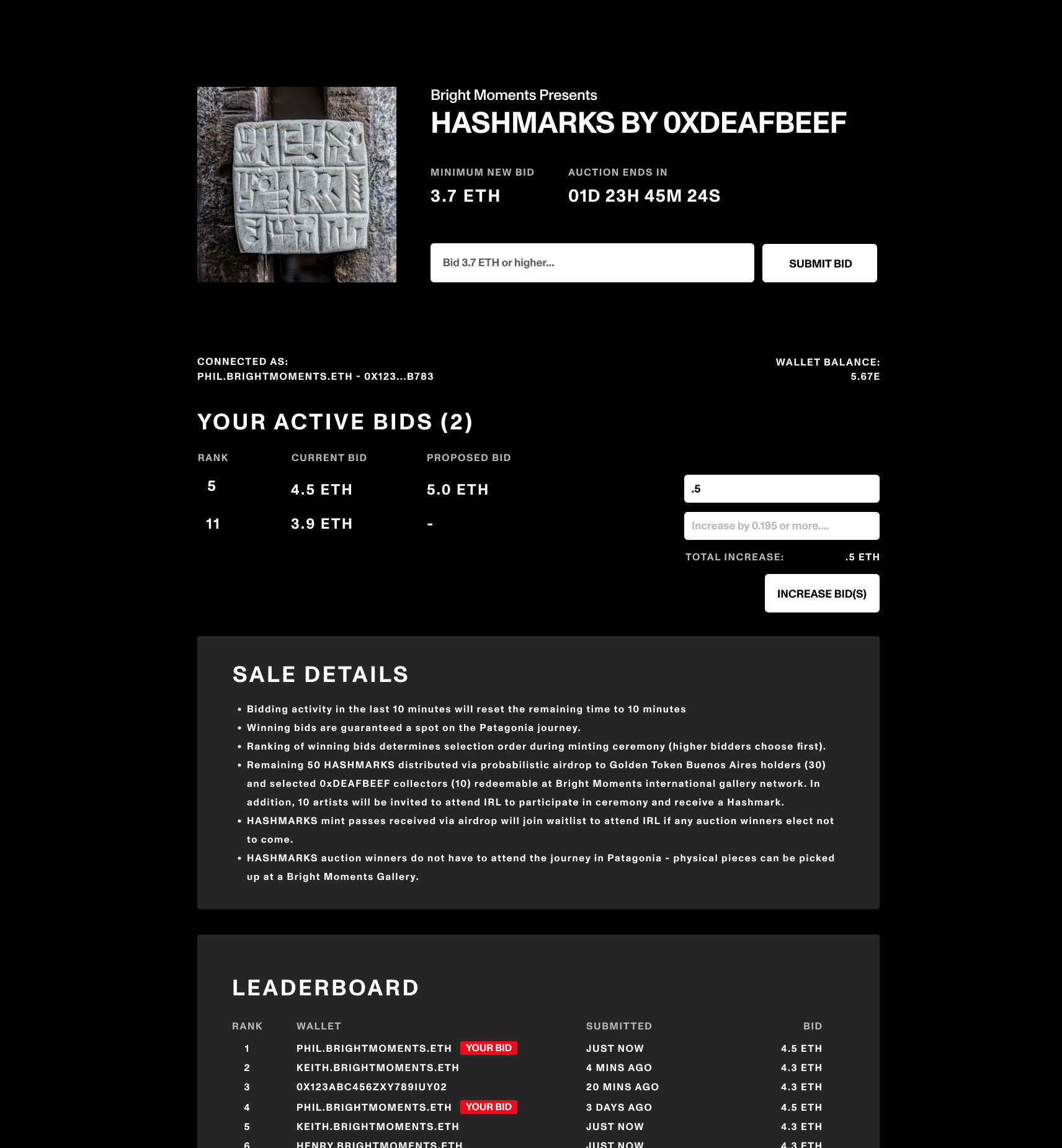

English auctions have a predetermined reserve price and a fixed bidding window. While the auction is live, bidders can submit a public bid. At the end of the bidding window, the top n bidders receive an output or the right to mint from the algorithm. English auctions are typically used for 1/1 pieces, but can be adapted for larger collections too.

English auctions work well when bidders are spread across multiple time zones, or when there is little or no existing price discovery for the work. Just like dutch auctions, english auctions can be combined with discounts and rebates to incentivize bidders and repeat collectors.

Platforms that use english auctions can also experiment with time extensions and minimum price increases to further improve price discovery, although introducing these variables can introduce complexity that may be unfamiliar to less experienced bidders.

In summary, determining the right sale type is a function of market demand, supply, and collector demographics.

Collectors

Collectors who are considering participating in a primary sale will often ask for the following information:

- Collection size

- Price

- Sale eligibility requirements

- Sale time

- Sample outputs

As the artist, it's up to you how much of this you choose to share. In general, it's better to err on the side of transparency, although there can be reasons to omit certain information (e.g. if you aren't comfortable sharing outputs before the sale, or if you're still getting feedback on price and want to maintain optionality).

If you are requiring that collectors hold certain tokens to participate in a sale, it's best to share this information clearly and publicly to avoid a situation where some people are acting on privileged information.

Collectors value consistency, fairness, and clear communication. Avoid doing surprise mints which can be mistaken for scams and try to give people a reasonable heads up if they need to be at their computers at a certain time.

Royalties

Royalties are dependent on the marketplace, but can provide a meaningful source of revenue for artists. In some cases, revenue from royalties can exceed that from the primary sale, so the decision to exclude them should not be taken lightly.

If you do choose to avoid enforcing royalties, you may want to consider withholding a larger percentage of the supply to align your incentives with collectors and provide you the opportunity to sell more work from the collection later on if there is price appreciation on the secondary market.

Marketing

Due to the pseudonymous nature of wallets, it's often hard to know exactly who your collectors are. This is especially difficult for new artists who haven't yet had the opportunity to develop personal connections with their holders.

To encourage visibility, consider posting about your project through social media or a personal website. Many generative artists write essays about the inspiration and methods behind the project, which can help educate collectors and drive interest in the collection.

Some examples include Tyler Hobbs’ Fidenza, Thomas Lin Pedersen’s Screens, Matt DesLaurier’s Subscapes, Proportio’s Eternal Harmony, Harvey Rayner’s Fontana, mpkoz’s Tectonics, Ben Kovach’s Edifice, Kjetil Gold’s Archetype, and Maya Mann’s Fake It Till You Make It.

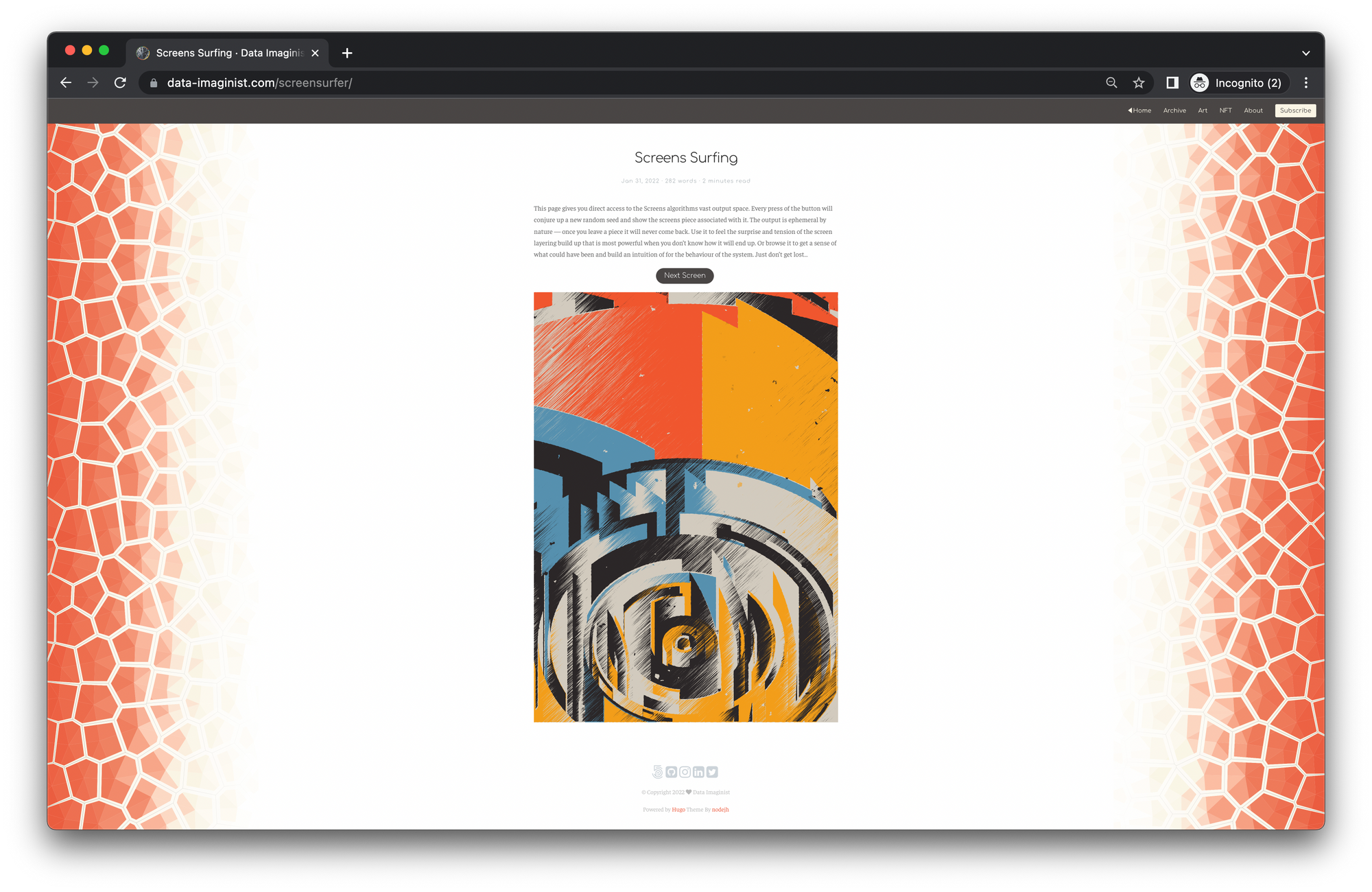

Sharing work in progress is especially helpful as a way to drum up interest for a collection. Creating a website which displays outputs from the algorithm and allows people to explore variations can also increase engagement.

When you're ready to announce your sale, choose a specific date and time and communicate it at least a week in advance (7 days is usually the sweet spot). If you have collectors who are not Very Online, consider sending them a personal note via email or text. Provide the link ahead of time from your official accounts (e.g. a pinned tweet) to discourage scammers from taking advantage of your audience.

In Summary

Sales can feel scary. As an artist, your speciality is creating the work. Selling it often requires a different skillset, one that feels uncomfortably like self-promotion and marketing.

Don't be afraid to ask for help from other artists who have done it before. Previous collectors are also good sounding boards and can provide feedback on price and collection size.

If you're considering your own generative art drop and have questions about structuring a successful sale, please don't hesitate to reach out at phil (at) brightmoments (dot) io

Thanks to Ben Kovach, Todd Goldberg, Adam, mpkoz, and Seth Goldstein for reading drafts of this essay.

Footnotes

[1] Credit for this tip goes to Ben Kovach.

[2] Special thanks to mpkoz, who pointed out the benefits of small collections in an earlier draft.